Slam Dunk: Commonwealth of Virginia v. Maryland, Take 2

riparian, adj.

a. Of, relating to, or situated on, the banks of a river; riverine. Freq. with reference to (the rights of) ownership of a riverbank.

--------

In 1996, the Fairfax County Water Authority sought a permit from Maryland for construction of a water intake pipe extending 725 feet from the Virginia shore. The pipe, which was above the tidal reach of the Potomac River, was designed to improve water quality for Fairfax County residents.

Maryland officials opposed the request, arguing that it would harm Maryland’s interests by facilitating urban sprawl in Virginia. The Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) denied the permit, holding that Virginia had not demonstrated a sufficient need for the offshore intake.

This marked the first time Maryland had denied such a permit to a Virginia entity. Virginia pursued MDE administrative appeals for more than two years, arguing at each stage that it was entitled to build the water intake structure under the Potomac River Compact of 1785 and the 1877 Black-Jenkins Award.

Four years after Fairfax County’s first request, in 2000, Virginia, still lacking a permit, sought leave to file a bill of complaint with the U.S. Supreme Court. That October, the Supreme Court referred the matter to a Special Master. In 2002, the Special Master recommended the Court find for Virginia, but Maryland filed exceptions to the Special Master’s Report. In December 2003, the Court overruled Maryland’s exceptions and granted Virginia the relief it sought.

Ronald Hoffman, director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at the College of William and Mary (and a native of Baltimore), served as an expert witness in the case for the State of Maryland. Hoffman uncovered evidence that, when the 1785 Potomac River Compact was negotiated at George Washington’s Mount Vernon home, the agreement applied only to the tidal Potomac and not to the waters above the falls, where Fairfax County is located.

Hoffman spoke with Xin “Evolet” Zhang and Julie King about his surprise when a majority of the Supreme Court justices dismissed his research and his argument. For Hoffman, the court case was a revelation about the difference between historical truth and legal truth.

--------

I don’t know who submitted my name [for the case], but I got a call from Adam Snyder [attorney for the Maryland Department of the Environment] about joining the effort. My books have all been about Maryland during the Revolutionary era, and I was well aware of the most important manuscript materials both published and unpublished that would bring to light the relationship between Maryland and Virginia and the long and at times acrimonious relationship between Virginia and Maryland regarding the Potomac River.

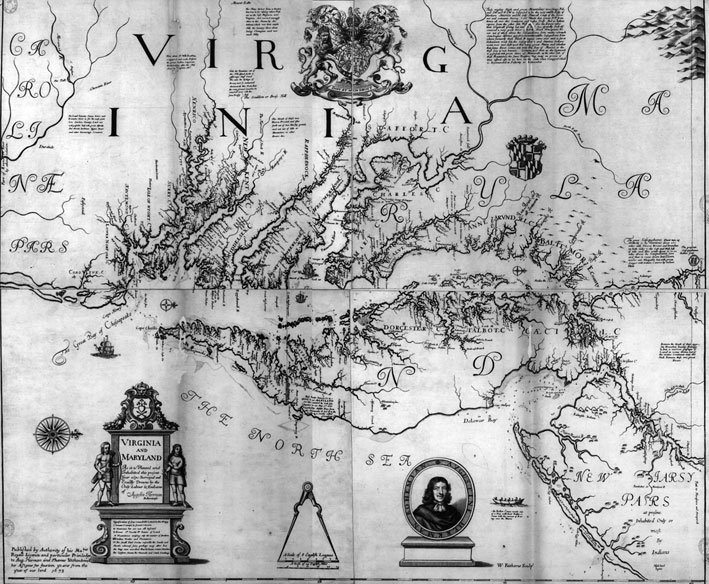

Adam had said that Virginia had built this water intake valve and that it was above the falls. That was the major consideration - that it was above the falls. Adam specifically wanted my input with regard to the Potomac River Compact [of 1785]. The question was, then, did the Potomac River Compact, which gave equal rights to use of the river by both sides, apply to the entire river or did it apply only to the part below the falls?

It was very clear to me, as it was to those who worked with me, that the Potomac River Compact only applied below the falls. No one was even thinking about the entire river at the time, in 1785. That was pretty clear from what [James] Madison said; and the other negotiators said. The river for them was the river below the falls and ocean-going traffic. Above [the falls] was the wilderness as far as they were concerned. And that was clear in their writing.

At first I thought there wasn’t much of an issue. I remember thinking, “This is a slam dunk; we’ve won this case.” I was sitting with Adam and some other people in his office, when they said, “You know, we think we have got a little shot here.” I was thinking, “What do you mean you’ve got a shot? It’s a slam dunk. I mean you’ve got Madison on your side; what are you talking about?”

I thought the State of Virginia had such a weak argument because they took the language of the Compact at face value. I prepared a paper that dealt with the context in which the negotiators thought about the Potomac River. The documentation, I thought, clearly, convincingly, and persuasively made the case that the Potomac River Compact did not apply to the river above the falls.

And the judge ruled against it.

The Special Master wasn’t the least bit interested in history as far as I could tell. I thought the guy was brain dead. Regardless of what Madison or the negotiators thought or wrote elsewhere, the “plain and simple language” of the treaty says the “Potomac River” and not the Potomac River below the falls. The whole river, not the tidal portion.

Later on, I talked to some friends who are attorneys, and they said that’s how the law works. [It was clear] Virginia held all the cards. It’s the language of the law, not the historical context. It was really shocking.

[My paper] would convince any historian, but clearly it would not convince any judge. And that was an eye-opener for me.