When the Surveyors Came Down

(Note: This essay appeared in The Tester Newspaper on February 14, 2013. The essay, Takings, explores the impact of the Navy's acquisition of the farms at Cedar Point in the words of those who experienced it.)

"That was the first we knew, when the surveyors came down."

On December 13, 1941, Richard Mattingly, 13, arrived home to find an eviction notice nailed to the front door of the family’s house on Susquehanna farm. “I’ll tell you how fast it was,” Mattingly later recalled in an oral history interview. “Pearl Harbor was on the seventh [of December, 1941] and the thirteenth we had the notice… It had everybody’s name listed, the farms they owned, the persons that lived [there], and everything. ‘You will vacate this property by the seventeenth of April 1942.’"

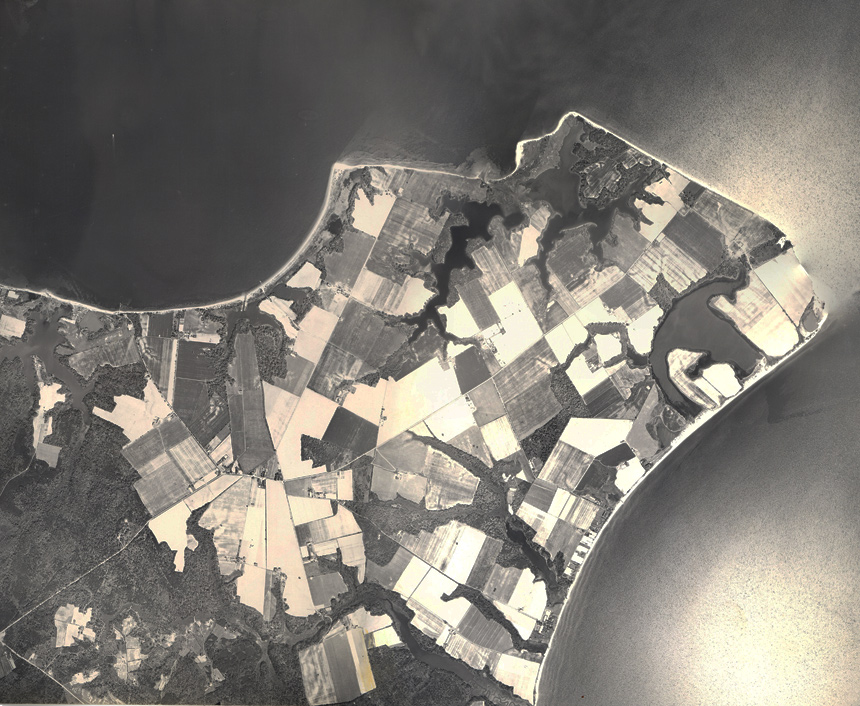

For 250 families of Cedar Point – today the Naval Air Station Patuxent River – the war had come home.

Nell Levay, who had grown up in Pearson, was away at college when her family received notice that the Navy was taking their farm. “Ours had four bedrooms and a bath and a hallway upstairs, plus the one-story kitchen attached right to the dining room. It lasted in perfect shape until that sad day came. It was a real heartbreaker when the Navy pulled in a bulldozer and bulldozed it to the basement and covered it up with dirt.”

Susquehanna. Pearson. Mattapany. Jarboesville. Fordstown. These were the names of the farms and communities at Cedar Point. And the order to vacate spared no one – everyone had to leave, and leave right away. The nation was at war.

“The people that had money could afford to go to court,” the late George Aud noted, and they got more money for their farms. “Little guy, he had to take what they gave him and try to find a place quick.”

The hardest hit might have been the laborers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and watermen. The government simply couldn’t compensate them for land that they didn’t own. For the small homes that they did have—appraised during the dead of winter—they were offered very small sums. Without the resources to sue the government, some of these people left the area entirely.

After the fence went up, the community was gone. Still, the husks of a community that once was remain: St. Nicholas Church is still used as a place of worship, Mattapany House, now known as Quarters A, houses the Commander of NAWC-AD, and the weathered ruins of Susquehanna House are a popular picnic ground.

The economy boomed. In the ten years following the opening of NAS Patuxent River in 1943, the population in St. Mary’s County doubled. By November 1942, 3,500-4,000 workers, most from beyond the region’s borders, lived in barracks while others found housing wherever they could: in rooms offered by locals, tar paper shacks, and even chicken coops. A trailer camp for workers stood where the Big Lots store is located today.

Local people, many who had subsisted on a dollar or a buck-fifty a day, found opportunities on base paying 87½ cents an hour.

The arrival of NAS Patuxent River spurred infrastructure improvements off base. Maryland Route 235, a two-lane gravel road following a centuries-old Indian path, was widened and paved in 1944. Electricity came, too, improving health and comfort, and changing lives, especially women’s lives, as power revolutionized household work.

Politics changed, too. For the old order in Leonardtown, then and now the county seat, the days of dominance were over. “Lexington Park, after the war, began to mature and started to seek political power,” the late Senator J. Frank Raley, Jr. recalled. “Leonardtown became very upset. Leonardtown had been the county seat, the controlling force in St. Mary's County. So when it saw this economic force beginning to gather [in Lexington Park], they began to see their power being taken away.”

Today, hardly anyone regrets the Navy’s installation at Patuxent River. The influx of money and improvements to public services lifted St. Mary’s County out of the remnants of an economic depression and an undeniable rural poverty. Without local support, the history of NAS Patuxent River in St. Mary’s could have been but a blip—a short term installation for wartime and nothing more. Today, it is one of the Navy’s most important facilities, the home of the Navy’s Test Pilot School and a major naval aviation testing facility.

--------

Click here to read more about how those people who were forced to leave Cedar Point remember the event.