Text: Maija Harkonen

Photographs: Bill Wood

U.S.-Russian Relations: Recalibrating Expectations

“One of the great achievements of Soviet-American relations of the 20th century was that we finished the Cold War without a big conflict,” said Professor Tatiana Shakleina from Moscow State Institute of International Relations, Russia, during her visit to St Mary’s College of Maryland (SMCM). In Dr. Shakleina’s opinion, the opportunity to build non-confrontational relations in the wake of the Cold War was squandered.

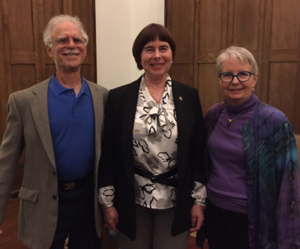

Tatiana Shakleina, Maija Harkonen

and Bonnie Green

Professor Shakleina gave a talk on U.S.-Russia relations on the SMCM campus on February 28, 2017 at the invitation of the Center for the Study of Democracy and The Patuxent Partnership (TPP). Bonnie Green, TPP Executive Director, welcomed Professor Shakleina to share with members of the local defense community, along with faculty and students, her views on on-going conflicts in Ukraine and Syria. Dr. Shakleina also met with students in Professor Matthew Fehrs’ class on U.S. Foreign Policy the following day.

Dr. Shakleina’s visit to the United States took place at time when U.S. lawmakers accused Russians of interfering in the U.S. presidential electoral process by hacking the computers of the Democratic National Committee and email accounts of Democratic Party officials. Russia has repeatedly denied involvement in the hacking.

Professor Shakleina’s presentation was appreciated as an opportunity to learn more about the values, fears, mindset and worldview held by Russians in general and Russian conservatives in particular. The mutual hostility and suspicion that characterizes U.S.-Russia relations benefit no one, yet the language of compromise is nowhere to be found. “Barriers to cooperation are substantial but as long as there is willingness to listen to each other, there is a chance that we can stop the downward spiral from getting out of hand,” Dr. Maija Harkonen, Executive Director of the Center for the Study of Democracy noted in her introductory remarks.

How Did We Get Here?

Rear Admiral Tim Heely, USN, talking with Dr. Shakleina at the reception.

The relations between the United States and Russia have reached their lowest point since the collapse of the Soviet Union. From the Western point of view, a new phase in the downward spiral started in March 2014 when Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea and started a proxy war in eastern Ukraine. From the Russian point of view, Professor Shakleina explained, it started earlier, when the United States led the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to expand to the Central and Eastern European countries thus undermining Russian national security interests. In the current stalemate, the two nuclear powers hardly talk to each other at the official level.

How realistic are the expectations that the Trump administration will manage to break the impasse and start improving relations between the countries? According to Professor Shakleina, President Trump made a number of statements during his presidential campaign that raised Russians’ hopes for better relations with the United States. Today, there is hardly any reason for optimism, Shakleina noted.

Economic Sanctions

Harry Weitzel, Chair of

College Foundation and

CSD Board of Advisors

In 2014, the United States imposed economic sanctions on Russia to punish it for annexing Crimea. Canada, Australia, Albania, Moldova, Iceland, Japan, Montenegro, Ukraine and 28 nations belonging to the European Union imposed their own sanctions on Moscow. Russia responded by banning imports of a wide range of U.S. and European foods.

Among other things, the U.S. sanctions targeted individual Russian officials and businesses and limited the availability of debt financing for certain Russian financial institutions. The European Union sanctions were also aimed at inflicting harm on the Russian economy. They included provisions such as placing restrictions on goods and services related to the oil industry. The Western sanctions caused considerable economic damage to Russia that was exacerbated by falling oil prices. In 2015 the Russian economy fell into a recession.

Perpetual Stalemate in the Cards?

During the U.S. presidential election campaign, many Russians supported Donald Trump, hoping that, if elected, he would lift or at least reduce the sanctions, Professor Shakleina said. These hopes are all but dashed. In early February, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley said that US sanctions against Moscow would remain in place until it withdraws from Crimea. The probe into Russian meddling in the U.S. electoral process is likely to make rapprochement between the two countries nearly impossible in the near future.

Is there any room to negotiate? The Russian officials have shown no desire to start negotiating about Crimea. “For Russia, the case is closed,” Professor Shakleina argued. In her view, the Kremlin was justified in “repossessing” Crimea where Russians constitute over 65 per cent of the total population. The peninsula had been part of Russia until 1954, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred it to Ukraine, she said. In 2014, when Russian President Vladimir Putin justified the annexation of Crimea, he challenged the legitimacy of Khrushchev’s decision.

Scott Zimmerman,

student reporter and

Nico Moore, Student Ambassador

The Western powers disagree with Moscow’s arguments. In their view, Russia had violated international treaties that it had signed. These include: the 1994 Budapest Memorandum; the 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Russia and Ukraine; and the 2003 Agreement between Russia and Ukraine on the Russian-Ukrainian border. The latter stated that Crimea was to remain an integral part of Ukraine. In the Western view, Russia also violated the Helsinki Final Act that obligates its signatories to respect the territorial integrity of each of the participating states.

Russia has not acknowledged that it violated international laws or infringed on the sovereignty of Ukraine when annexing Crimea.

Limited Cooperation

Ukraine and the issue of economic sanctions continue to be stumbling blocks for future dialogue between Russia and the United States. Yet, Americans and Russians still meet and discuss various issues at official forums, such as the Arctic Council, and there are numerous interactions among individuals of both countries. Global issues affect them equally and the countries hope to find common ground in preventing the spread of terrorism and nuclear weapons. In addition, bilateral commercial relations among businesses continue, albeit at vastly reduced levels.

Even at times when much of the official cooperation between the United States and Russia is at a standstill, contacts between their peoples should be encouraged, Professor Shakleina emphasized. She believes that Russia and the United States need to enhance their efforts at public diplomacy, including such activities as educational exchanges and personal contacts. Broadening dialogue between citizens and institutions of both countries helps increase understanding of the concerns, fears and aspirations both have. “Americans are willing to have better relations with Russia,” she concluded with reference to her own decades-long friendships with American people.

Cecile Walton and Kezia Osunsade contributed to this article.

- Students

- Dr. Regina Faden, Dr. Shakleina

- Tom Daugherty

- Inquiry

- John Giusti, Tatiana Shakleina, Sherry Stanley

- Michael Cain